How Factory Jobs Help Bangladeshi Women

According to a September 2014 research brief from The Cato Institute, “Access to factory jobs significantly lowers the risk of early marriage and childbirth for girls in Bangladesh, and this is due to both girls postponing marriage to work in factories and to girls staying in school at earlier ages.” Despite the documented dangers and harsh working conditions of garment factories in developing countries, the authors explain that the increase of such jobs in Bangladesh has had a profound effect on young women in the areas of education, marriage, and childbirth. These jobs require a decent level of numeracy and literacy and thus, girls stay in school longer to learn as much as they can to go after these jobs. With this, comes a higher level of education and a delay of marriage.

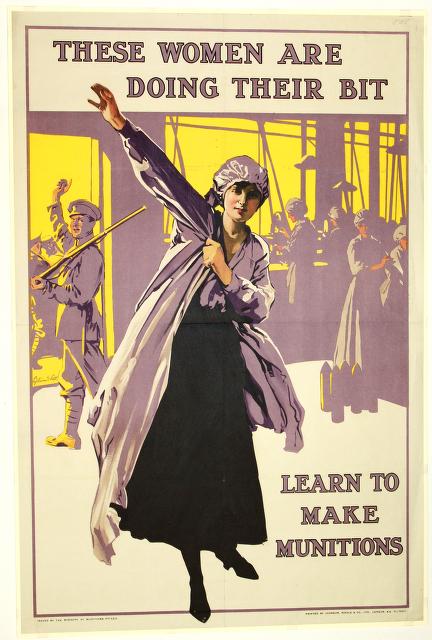

As I’m also taking a class in the Upheavals of War, I am reminded of the vast redefinition of gender roles during World Wars I and II, when women gained newfound freedoms and responsibilities outside of just being wives and mothers. As all of the young and able-bodied men were sent off to fight, women kept calm, carried on, and took up the jobs necessary to the functioning of daily life. Work needed to be done, whether on the farms or in the factories, and only women were left to do it. Women were eager to assume these roles – wanting to contribute to the national war effort and also, to gain a kind of independence and respect outside the home that they had never experienced before.

Life for European and North American women changed as they saw themselves capable of achieving more than domesticity during this time, and they seized the opportunity. In present day, women around the world still struggle to escape the disadvantages of their gender; particularly in South Asia, where child marriage is still prevalent.

A report I came across by Human Rights Watch states that “Bangladesh has the fourth-highest rate of child marriage in the world,” where about 65 percent of girls are married before age 18. Child marriage is usually bred out of economic poverty and perpetuates it, along with other ills such as spousal abuse and the increased likelihood of death in childbirth. Along with these, I add the noted cultural stigma of being viewed as “less than” if not married by a certain age. However, in Bangladesh and other impoverished nations, this age is much lower than in the West, resulting in dire circumstances for very young girls. Bangladeshi girls are beholden to this cultural practice and are made to accept their fate, despite not being mentally or physically ready for married life. Additionally, most are forced to cast away their hopes of attending or continuing school. I can relate to this in a way. At 19, I was pressed to consider an arranged marriage because I was not able to move on to college after graduating high school. I protested and declined, and eventually ended up working for several years before being able to attend college. I was able to hold on and wait for my higher education opportunity, but not many disadvantaged women get to do this.

As the research states, there is a correlation between higher educational attainment and the postponement of marriage. I believe that if impoverished women can stay in school longer, and later, acquire jobs to sustain themselves, they are seen as less of a burden upon their families in terms of finances and protection. Like wartime jobs in Europe and North America, the garment industry in Bangladesh is providing a means of independence and security that these girls have never experienced, and might prove to be the key to the advancement of women in this particular region.